Katherine Anne Porter (1890-1980)

Mike the letter-carrier left a hefty package on my front porch on Saturday. I smiled when I found it there, for I knew what was in it: eight beautiful, mint volumes of the Library of America, snapped up for a song (roughly five bucks apiece) in an eBay auction. So cheap were they that I could absorb the inconvenience that I already owned two of them, which will now grace the growing libraries of one of my children or friends. Sometimes you gain so much on the straightaways that you can easily absorb the delays occasioned by the roundabouts.

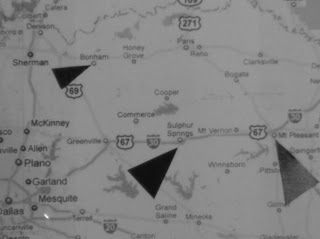

I had been expecting the books, but was not prepared for the return address. It turns out that I had bought them from a private party in Sulphur Springs, Texas. That may mean little to you, but we used to play those guys in football. My noble but fiscally calamitous, rainbow-chasing parents dragged me through eight schools in five states. Where they dragged me to in the fall of 1952 was an East Texas town called Mount Pleasant and the high school that became my alma mater. Sulphur Springs was about forty miles west, and for us it meant the real boondocks—an attitude doubtless reciprocated by the Sulphurians, who were, after all, that much closer to Dallas.

Actually most East Texas towns of that era looked pretty much like “Anarene” in The Last Picture Show, except that there wasn’t nearly that much sex around—a sad reminder of the crucial difference between fact and fiction. But Sulphur Springs had a special proverbial distinction among the regional Hicksvilles and Nowhereburgs. America’s greatest humorists have ever been its real or pretended provincials; and the parodic boast “I’ve been to the Sulphur Springs Fair”—with or without an added “twice”—was a mocking claim to exotic experience and deep sophistication.

East Texas: more like the Deep South than the Wild West

Mount Pleasant is the seat of Titus County, Sulphur Springs of Hopkins County. About fifty miles northwest of Sulphur Springs is Bonham, seat of Fannin County, the third point in these triangulated memories. Fannin County was the birthplace of one Great Man (Sam Rayburn, the legendary Speaker of the House); one Bad Man (John Wesley Hardin, the legendary outlaw); and at least one very Good Woman (Cora Louise Nelson Davidson, my maternal grandmother). Born in 1873, she spent her earliest years on the Red River, the border between Texas and the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). She was orphaned early, and sent back east to an Episcopal school in Terre Haute, Indiana, long since defunct, to prepare to be a teacher. By the age of twenty or twenty-one she was half of the “school system” in Salida, Colorado.

From Shadow to Reality: Cora Louise looks back over Four Generations

Indeed I had always supposed her to be a native of Colorado. She revealed to me her Texan origins, which she seemed to regard as slightly shameful, only when I myself moved there. We have a few things from her, now transferred in trusteeship to her great-great granddaughter Cora Louise Fleming-Benite (born 2004), including her baptismal spoon. Since little Cora has had all her schooling in France, she probably has not needed another of her ancestor’s relics, an elementary French grammar, which begins with a lesson on how to engage a fiacre (a horse-drawn carriage) at a Paris train station.

What all this Texas stuff is in aid of is the prize book in my package of prize books from Sulphur Springs: Library of American # 168--Katherine Anne Porter’s Collected Stories and Other Writings. Of course I already owned editions of her most famous story collections—Flowering Judas and Pale Horse, Pale Rider. There is no better writer of short fiction in the English language, period—an utterance of critical “extremism” I am willing to defend. But many of the “other writings,” which are not easy to find, are likewise gems, and I am delighting in them.

Porter was born in the hamlet of Indian Creek, Texas, in 1890; she lived in the Lone Star State until early adulthood; and Texas is a recurrent theme in her writings. Her attitude toward Texas was not unlike that of my grandmother, who could have been her older sister. On the other hand she loved Mexico, and lived there as much as she could. Two short essays of particular poignancy are “Notes on the Texas I Remember” and “Portrait: Old South”. In the former she tells in her beautiful lapidary prose a horrible anecdote of a group of poor Hispanics ejected from a religious revival in Kyle, Texas, about 1897, on account of being poor and Hispanic. She died in 1980. I wish she could have accompanied me in spirit to my amazing fiftieth high school reunion, organized, naturally, around a home football game. In 1954 the schools in East Texas were still racially segregated. In 2004 many of the Mount Pleasant Tigers—including the guy who seemed to rule their backfield—were black. Half of the high-kicking majorettes—a group hardly less important in the aristocracy of a Texas high school than its football stars—were Latinas. People who think things never change sometimes need to think again.

Katherine Anne Porter knew most of the American literary greats of the 1920s and 1930s. Like many of them she was a “left-wing intellectual” deeply engaged in our nation’s spectacular injustices and the strange insecurities that gave birth to the Red Scare of 1919, sadly reborn in another form three decades later. Yet her great political masterpiece, so far as I can tell, was written in 1977, when she was eighty-seven years old! It is her brilliant memoir—she calls it a “story”--fifty years out, of the agitation surrounding the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti in August, 1927. Everything about it is perfect, beginning with its title: “The Never-Ending Wrong”. How can it be that I never came upon this essay while I was writing The Anti-Communist Manifestos?

The never-ending wrong is the larger meaning of the possible judicial murder of two immigrant Italian anarchists; but there are other wrongs, including the shameful arrogance of blind political superstition. “It is hard to explain, [she writes] harder no doubt for a new generation to understand, how the ‘intellectuals’ and ‘artists’ in our country leaped with such abandoned, fanatic credulity into the Russian hell-on-earth of 1920. They quoted the stale catch-phrases and slogans. They were lifted to starry patriotism by the fraudulent Communist organization called the Lincoln Brigade. The holy name was a charm which insured safety and victory. The bullet struck your Bible instead of your heart.” I have rarely encountered such wholeness of vision—and I’ve been to the Sulphur Springs Fair, twice.

Her every page bears the stamp of genius